I’m Offended with Political Correctness

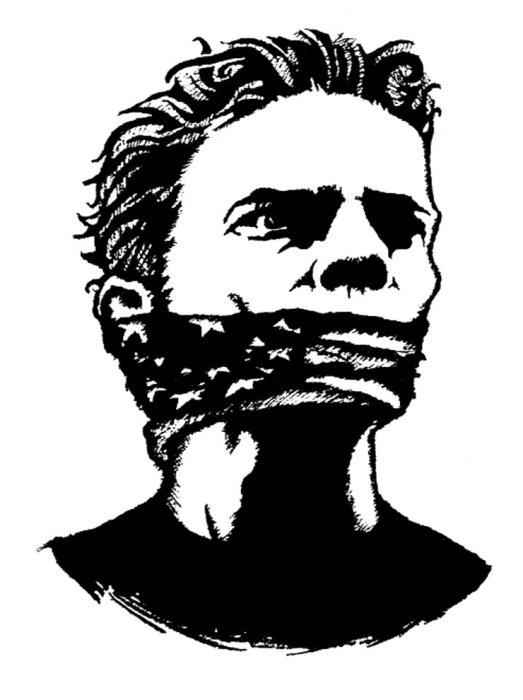

Political correctness is an issue that college students like to gripe about (at least when it affects them) but doesn’t seem to actually harm anyone. So, what’s the trouble in being considerate of others? Better to be safe than sorry. Well, despite popular belief, and perhaps to the pleasant surprise of the inarticulate griper, I think there is a very real case to be made for the real harms of political correctness. Especially when it is valued above other considerations or at the expense of other considerations of expression on campus.

We can clearly identify who is hurt when we are not politically correct. The loudly offended make it clearly known that their feelings have been injured by careless words. But who, exactly, benefits from this kind of speech? And who is hurt when it’s restricted? As I mentioned, we all realize on some instinctual level that we are being restricted, and it is uncomfortable. That is, the claim that political correctness is an unchallengeable good cannot be true. Taken from the perspective usually afforded to free speech in the modern world, this means the burden falls to the argument for restriction rather than against. The fact of restrictiveness necessarily puts the ball in the court of those who would have us tip-toe around our words. Even so, the case has been made that political correctness is the “modern” way to be. Though we are often uncomfortable when it restricts our own speech, it seems only proper that from a position of righteous condemnation we should restrict speech in general in order to reach some “higher” standard for dialogue.

We can clearly identify who is hurt when we are not politically correct. The loudly offended make it clearly known that their feelings have been injured by careless words. But who, exactly, benefits from this kind of speech? And who is hurt when it’s restricted? As I mentioned, we all realize on some instinctual level that we are being restricted, and it is uncomfortable. That is, the claim that political correctness is an unchallengeable good cannot be true. Taken from the perspective usually afforded to free speech in the modern world, this means the burden falls to the argument for restriction rather than against. The fact of restrictiveness necessarily puts the ball in the court of those who would have us tip-toe around our words. Even so, the case has been made that political correctness is the “modern” way to be. Though we are often uncomfortable when it restricts our own speech, it seems only proper that from a position of righteous condemnation we should restrict speech in general in order to reach some “higher” standard for dialogue.

There are several issues with how this plays out. The most primary is that any restriction on speech necessarily retards our ability to express ourselves fully. Take a look at that last sentence again, for example. I use the verb to retard in a classic way. Grammatically correct, often used, almost scientific in definition. Yet on some campuses this sort of use would be called into question. I use the word not as a slur to the mentally disabled but as a description of the restraint of expressive growth. There have been campaigns here and elsewhere that have been so successful that people literally forget the original meaning of the word or phrase in question. The point at which these campaigns are causing us to actually lose words should be of concern at least to our English departments. In fact, I’ve found sometimes it actually impedes my ability to discuss in class and elsewhere the very issues that led to these considerations. If I make a statement about “women,” does this make me a misogynist? I certainly don’t think so. God forbid the issue of the men’s rights response to feminism be brought up, despite the fact that this is a serious contemporary issue having much to do with our societal psychology and possibly posing one of the most complex issues of the day. When trying to make a point about the complexity of society and gender roles and the effect of this on men, I find more often than considering the issue, my classmates implore me not to “trivialize” the feminist cause.

But the issue is deeper than this. Why should we speak our minds? Why should we not only allow but also invite discomfort at expressions and ideas? I see two important facets being lost to discussions. One is the challenging and broadening of the collective understanding of correctness. The other is of addressing internal feelings, thoughts, biases and intentions and challenging these as well.

A culture of restriction, let alone a solid regulation against certain types of speech and expressions conditions us not to speak our mind and to conform to popular opinion without challenging it. This means that whoever is setting the terms for what is correct and what isn’t (be it those in power, the majority, or the loudest most offended faction) has a monopoly on what is considered offensive. Just as we would caution a university not to prescribe any particular moral belief system or value set, I would caution against assigning a definitive set of acceptable expressions for the same reasons. It presupposes that the university’s definition of what is acceptable is infallible. In the interest of erring on the side of expression, we should avoid this outcome. Part of the purpose of college life is to challenge what is accepted both in the main and by the individual. If we never say anything that offends anyone, how can we ever challenge those mainstream sensibilities? I’m sure that the things a civil rights activist would say offended many in the Jim Crow South. Conversely, when an individual holds beliefs that we would hope would be challenged, keeping these to themselves prevents the issue ever being fully addressed. The silent racist is still racist; they just never have to hear the arguments against their views. In the interest in challenging ourselves and our society, I think we must always err on the side of expression. Regimes of predetermined correctness and even particularly stifling cultures in the same vein prevent this from being the case and undermine our ability to learn and change.

A culture of restriction, let alone a solid regulation against certain types of speech and expressions conditions us not to speak our mind and to conform to popular opinion without challenging it. This means that whoever is setting the terms for what is correct and what isn’t (be it those in power, the majority, or the loudest most offended faction) has a monopoly on what is considered offensive. Just as we would caution a university not to prescribe any particular moral belief system or value set, I would caution against assigning a definitive set of acceptable expressions for the same reasons. It presupposes that the university’s definition of what is acceptable is infallible. In the interest of erring on the side of expression, we should avoid this outcome. Part of the purpose of college life is to challenge what is accepted both in the main and by the individual. If we never say anything that offends anyone, how can we ever challenge those mainstream sensibilities? I’m sure that the things a civil rights activist would say offended many in the Jim Crow South. Conversely, when an individual holds beliefs that we would hope would be challenged, keeping these to themselves prevents the issue ever being fully addressed. The silent racist is still racist; they just never have to hear the arguments against their views. In the interest in challenging ourselves and our society, I think we must always err on the side of expression. Regimes of predetermined correctness and even particularly stifling cultures in the same vein prevent this from being the case and undermine our ability to learn and change.