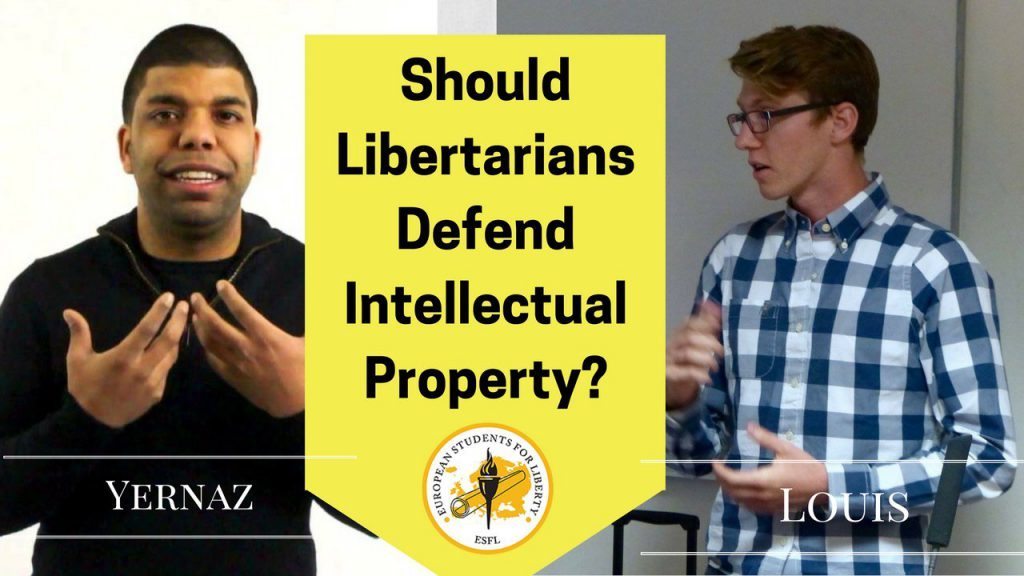

Liberty Face Off: Intellectual Property?

In this third edition of ESFL’s Liberty Face Off, Yernaz Ramautarsing and Louis Rouanet will delve into the long lasting libertarian debate on the issue of intellectual property rights. Is intellectual property a thing, and if so should libertarians defend it?

Do you have an issue in mind that you would like to see debated among libertarians? Please e-mail [email protected] and your suggestion might be discussed in the next Liberty Face Off.

Man has a right to the product of his mind

by Yernaz Ramautarsing

If libertarians care about property rights, they should defend and advocate for intellectual property. In order to do this they must shed their physical-immaterial property false dichotomy and better understand the nature of rights.

Why you may ask? Shouldn’t only physical objects count as property? To understand this argument we need to get to the nature of rights and understand that all rights are in essence property rights. These rights are not granted by any government or creator, but they are ‘’secured’’ by a government. Ayn Rand, who was a fierce advocate of intellectual property, said it best:

“Patents and copyrights are the legal implementation of the base of all property rights: a man’s right to the product of his mind”

This is what the entire intellectual property discussion boils down to: Does a man have a right to the product of his mind? All other disputes about trademarks and the duration of copyright don’t address the essential moral question at hand.

If man has a right to the product of his mind, no other man has that right without consent from the originator. This is why Lady Gaga rightfully ‘’owns’’ her songs and why any of us ‘’copying’’ or ‘’downloading’’ them, are guilty of an act of theft.

The anti intellectual property protesters will argue that you cannot steal something if it isn’t scarce. This line of reasoning is quite bizarre: stealing without someone ever noticing is theft all the same. Furthermore, things that are not physical can be worth way more than physical objects. One new Beyonce single can be worth more than a luxurious sportscar. Therefore the false physical-immaterial dichotomy used by some libertarians as a wedge to take‘’free stuff’’ does not hold up.

Context matters. Writers, artist, poets all create intellectual property with a certain goal, which is widely understood: making money. The feeling of entitlements under a certain strain of libertarians is hedonistic and startling.

No artist owes you an album, no actor owes you a movie. Paying people for their skills will be positive for the literature and entertainment industry as well as for the customer. Paying for your entertainment consumption will make more critical customers. These will influence the industry to take their preference into account. All those illegal downloads don’t communicate this preference to this industry. The free market has showed via Netflix, HBO and Amazon that if we are willing to draw our wallets, the industry will respond with a better product.

Then there are the open source advocates, they claim that their system is superior. I challenge them and wish them success. If the market agrees with them, then maybe IP will become a thing of the past. Wikipedia (founded by Objectivist Jimmy Whales) sets the right example. It is also necessary to clarify the pro intellectual property position, again invoking Ayn Rand on the difference between ideas and their material form:

“An idea as such cannot be protected until it has been given a material form. An invention has to be embodied in a physical model before it can be patented; a story has to be written or printed. But what the patent or copyright protects is not the physical object as such, but the idea which it embodies. By forbidding an unauthorized reproduction of the object, the law declares, in effect, that the physical labor of copying is not the source of the object’s value, that that value is created by the originator of the idea and may not be used without his consent; thus the law establishes the property right of a mind to that which it has brought into existence.”

In closing I would love to add that the role of the mind cannot be underestimated. I warn libertarians not to fall in the Marxist trap of thinking that production originates in our hands instead of our minds.

Intellectual property comes down to intellectual monopolies

by Louis Rouanet

Libertarianism is the political philosophy according which social life must be based on liberty -i.e. on the absence of any aggression against one’s person or rightly acquired property. Therefore, the fundamental question for the libertarian is not whether or not he should defend intellectual property but rather whether intellectual property is property at all. If you believe, as I do, that ideas are not subject to property rights, then it is not possible as a libertarian to defend what is wrongly called “intellectual property.”

Private property comes from two factors. The first is that as only individuals have control over their body, the most conclusive way to organize social life is to respect them as self-owners. As self-owners, they are entitled to the product of their labor, hence property rights. The second factor is that as some means are scarce, assigning property rights to them becomes necessary to avoid conflicts and organize social life.

Ideas, however, are not scarce. Once discovered, the usage of an idea by one individual does not, in any case, hamper another individual’s use of this same idea. No conflict over scarce resources can occur in the realm of ideas as long as the government does not grant a monopoly right to the benefit of some private interest.

Intellectual property simply cannot be “libertarian” as it is by its very nature opposed to the philosophy of self-ownership. Pushed at its logical conclusion, intellectual property means nothing else than to have a right over somebody’s mind and creative genius since only the first to discover an idea can claim “intellectual ownership” over it.

But such an intellectual monopoly is not only unfair, it is also economically inefficient. First, it reduces competition today, thus making the economy less efficient. Second, innovation and intellectual creation are the result of a cumulative process in which individuals copy and improve existing products. Initial innovations are never perfect, and must be complemented by further innovation in order to reach their full potential. For instance, when Oprah Winfrey interviewed Ralph Lauren in 2011 and asked him “how do you keep reinventing?” Ralph Lauren answered “You copy. Forty-five years of copying; that’s why I am here.”

Giving privileges to the first innovator will destroy this cumulative creative process and lead to fewer inventions, not more. The innovative process is, for the most part, a product of human action but not of human design. Hence, it is often hard to know who the true inventor of a new technology is. For instance, there are no fewer than twenty-three people who deserve credit for inventing some version of the incandescent bulb before Edison. Similarly, consider the fact that Elisha Gray and Alexander Graham Bell filed for a patent on the telephone on the very same day. More often than we think, the reward brought about by patents is arbitrary.

The great French Classical economist Michel Chevalier, as one of the most ardent free-trade advocates, explained the conservative and anti-innovation nature of monopolies in his Les Brevets d’Inventions (1878). According to him, patents and the guild system, by destroying competition and the freedom to enter into markets, are similar in nature and deter rather than foster innovation. Today, the juridical instability associated with patent trolls and the millions of existing patents tends to cause more harm than good to the real innovator. It is then no surprise that a growing literature is sceptic toward the alleged virtues of intellectual property. Among others, Boldrin and Levine in Against Intellectual Monopoly, argue that intellectual property does not increase the rate of innovation even in the pharmaceutical industry and should be abolished.

But even if patents and copyrights were real property, it would still be unlikely that such “property” could ever be enforced without a State apparatus. The very existence of such an apparatus, on the other hand, implies a violation of property rights as it must be financed by coercive means -i.e. taxation. This in itself, would be inconsistent with libertarianism.

These pieces solely express the opinions of the authors and not necessarily the organization as a whole. European Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, please contact [email protected] for more information.