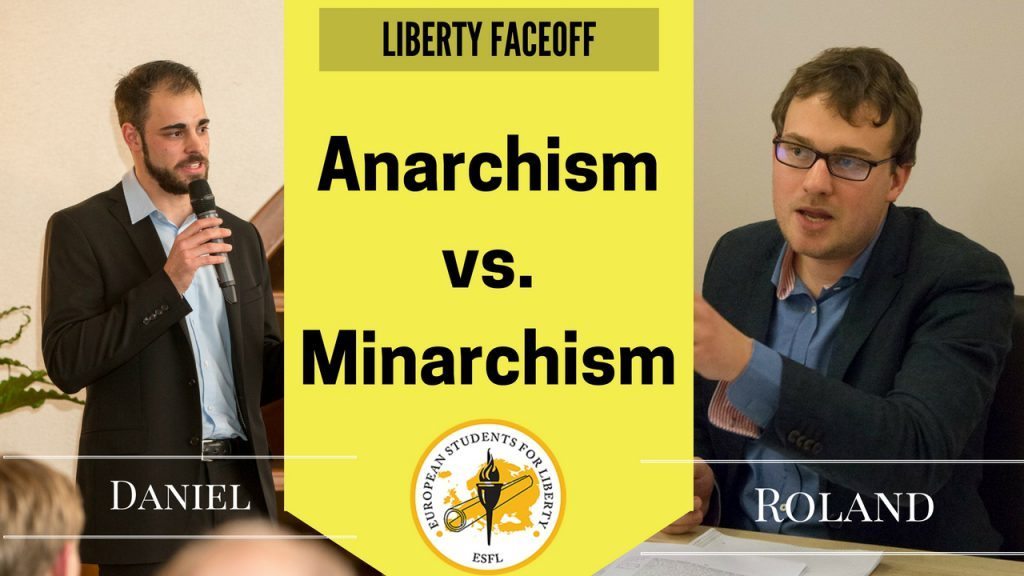

Liberty Faceoff: Anarchism vs. Minarchism

In this fourth edition of ESFL’s Liberty Faceoff, Daniel Issing and Roland Fritz will delve into the long lasting libertarian debate between anarchism and minarchism. Should we strive for a society free of government, or do we need it to safeguard our liberties?

Do you have an issue in mind that you would like to see debated among libertarians? Please e-mail mhemelrijk@old.studentsforliberty.org and your suggestion might be discussed in the next Liberty Faceoff!

Anarchy better safeguards liberty than small government

by Daniel Issing

Whenever people learn about my anarchistic leanings, it is almost guaranteed that confusion and irritation will ensue. Political pundits left and right regularly invoke nightmare scenarios of unleashed mayhem, destruction and disorder, should anarchy break loose. And indeed, if you equate anarchy with a lawless society and the absence of rules, the conclusion follows almost directly. Is anarchy thus nothing but a utopian, but fundamentally mistaken projection of the ideals of young radicals into society?

To understand why this need not be the case, it’s instructive to look at a problem that an ultra-minimal state – whose only functions include the police, courts and the military – cannot possibly surmount: the problem of The Myth of the Rule of Law. This is the idea that there can be such a thing as “a government of laws and not of people”, as John Adams put it. Following John Hasnas’ detailed analysis of the character of legal reasoning, the presumption that we can unambiguously deduce clear rulings from the law is sadly mistaken. Legal reasoning doesn’t work like mathematics, where one can derive an immense number of principles and applications from a few axioms. Instead, it is perfectly conceivable to reach two mutually contradictory conclusions from it.

What conclusions you will derive from the given law, will depend heavily on what you think the law should be – in other words, your political preferences. Should the law be used to preserve the integrity of traditional social institutions, such as the family and religion, as conservatives would argue? Should laws serve as mechanisms to ensure equal opportunities, as many on the left claim? Is their purpose to guarantee a maximum of personal autonomy, as libertarians would demand? You will find confirming as well as disconfirming evidence for either position in the body of law and actual court rulings.

Now, the peculiar thing about the law as we know it, is its monopolistic character. In short, this means that whichever interpretation will be established as the dominant one hence becomes applicable to all subjects of the jurisdiction. Thus, there are strong incentives for each group to seize control over the interpretation of the constitution. Following standard insights from the Public Choice School, it is not unreasonable to expect people to be strictly self-interested when it comes to politics, especially when the stakes are high. Given the enormous influence and power that the winning coalition will possess, even the most definite constitutional limits will in the end not prevent the takeover of a once-benign state by special interest groups.

Nor is it very likely that lovers of limited government will win the race. For consideration: while it is true that liberalism has made the (Western) world richer than our ancestors could ever imagine, this statement is only true on average and in the long run. Markets do not generate instant gratification for a given individual, and there’s no guarantee that one’s business plans will be successful. For the politician, much more direct means towards personal enrichment are available, like rent seeking and tax revenue.

The tendency of initially minimal states to outgrow their narrow limits can best be observed in the case of the US: inspired by classical liberalism and starting off with a real federal spending of $60 per capita, the country now regulates wine labelling and spends more than $11,000 per capita, or roughly 200 times as much as in 1792. Democratic checks and balances won’t be of great help either, largely because of rational ignorance on behalf of the electorate. But why would an anarchistic society do better? I cannot offer more than a very schematic answer, if only because I would have to outguess the future to present a more detailed image. Lacking a sufficient number of historical forerunners, the best we can hope for is to confine ourselves to general observations.

Fallible humans that we are, we can hardly expect that we just “know” what the best law would be. Uniformly imposing one set of laws on an entire country, deprives us of the opportunity to use the full potential of trial and error. Instead, you get one-size-fits-all, democratically tailored towards the median voter. Worse yet, errors would affect a much larger group of people, who at best can opt to move to another country. As this usually includes high exit costs – both financially and socially -, nations as the providers of a legal framework can expect to keep most of their “customers” even though the “service” they offer is of dubious quality.

Libertarian anarchists instead propose that this job is taken over by privately-owned defense agencies, possibly intersecting territorially, which offer their policies on the market like any other good. In the tradition of Hayek, I would argue that this allows us to put the available, dispersed knowledge to best use – knowledge that cannot be possessed in its entirety by a single governing body. Add a little competition to that for effective checks and balances, and you likely get a system that outperforms the one we’re all too familiar with in at least two important respects: product range and product quality.

Before I end, let me say a few words about the much-cited apprehension of gang warfare between competing defense agencies. Two possible scenarios: a) One or several agencies try to gain dominion by annihilating all other competitors in a geographic area and b) a conflict over a case involving patrons of more than one agency, escalates into armed fighting. Both of these would lead to Somali-style anarchy. Neither, to be sure, can be ruled out with certainty. But thankfully, there exists a mechanism to counter these tendencies: the price system. Its beneficial impact is to be found in the fact that it forces agencies to economize on the means they employ. Physically attacking a competitor, for instance, will have to be paid for through assets or by increasing membership premiums. And as assets are finite, sooner or later customers would have to foot the bill – but isn’t that radically at odds with their financial self-interest?

What’s wrong with anarchy?

By Roland Fritz

In short: a lot! In this essay I want to highlight the problematic nature of anarchic conceptions of libertarianism and demonstrate why building a vision of liberty that excludes any role for state-action is likely to be a mistake.

Coming in, let me briefly define, in order to avoid misunderstanding, how I understand the concept of anarchy, namely as a social order that functions without a monopoly of force, i.e. a state.

My 1st and most obvious objection to anarchic forms of political organization is rooted in history, namely in previous experiences with anarchy – or, to be more precise, the lack thereof. Supporters of anarchy often either point to merely theoretical justifications for anarchy, or reference some minor instances of (semi)-anarchic societies that supposedly operated moderately effectively, the most prominent among them being medieval Iceland.

This is all well and good, but I do not think it greatly helps us with the building of free and prosperous societies in the present. The facts are this:

1) No known society has ever significantly increased its standard of living under anarchy.

2) Almost every example of anarchic political organization that at least worked tolerably well pertains to small, somewhat isolated and highly homogeneous societies.

3) Many instances in which anarchy was the dominating form of political organization for some time (i.e. Albania 1997 or the Russian Civil War) actually generated terrible results in terms of economic development and individual liberty.

Connected with this argument is a second point: namely the one concerning the persistence of anarchy: Even if one could somehow (magically) introduce anarchy, or if it had ever been durably realized in history, there are good reasons to assume that social forces will necessitate an anarchist society to return to state-like forms of governance over time. Not only do people differ in their abilities and skill-sets, they also differ with respect to their preferences for individual autonomy and demand for authority put over them. It is to be expected – and history would clearly side with me on this point – that in the course of time, anarchic orders will show a tendency to be transformed into structures that come to occupy a monopoly of violence yet again.

Also relevant is the the question of how anarchistic entities could ever persist in an international order that is not fully anarchic, which would entail the constant threat for anarchist societies to be subsumed by territorial rivals with functioning monopolies of force.

My third objection to anarchy is a very practical one: As libertarians we have to accept that we are, at the moment, living under conditions that are very different from any conceivable notion of libertarian utopia. That also means that some groups of people in western societies have learned to rely on state-action for their security and livelihood.

The question of how to help those groups or how to best compensate losers of a transition to anarchy, who had deservedly formed expectations according to the status-quo, is a tricky one. In my mind, it also constitutes a strong imperative for not focusing on anarchic conceptions too much.

Paraphrasing Steve Horwitz, one could say that libertarians should not attempt to take people’s crutches away (i.e. the [welfare] state) before having healed their bones, i.e. enable them to earn a decent living in private markets, which involves both legal changes and long-term adjustments in motivation and outlook on life.

Here the notion of a small, efficient state gradually reducing its size and scope is the more desirable vision for me. Thanks to scholars in the tradition of Public Choice we do have vast insight into the requirements and “Do’s and Don’ts” of government rollback, which makes this option much more desirable than some vague hope that anarchy might somehow be introduced and made work.

As an additional, merely practical point, it should be stated that at the given time there is – historically speaking – actually less necessity for anarchy than there has ever been. This is because people’s opportunities to work around governmental organizations and restrictions are, thanks to globalization and technological innovations, bigger than they have ever been. Think: Uber instead of government-backed taxi-monopolies, private arbitration courts, etc.

Connected with this is the point that western civilization seems to have found a pretty form of governance already: constitutional democracy. The empirical facts are quite clear: generally speaking, democracies are richer, freer, more peaceful and less violent than other hitherto known forms of governance. Due to the lack of practical experience with anarchy, wouldn’t it be extremely risky to forego this functioning, albeit imperfect, form of political organization for an alternative with which we do not have any practical experience?

Furthermore, as another practical point, excessive focus on the workings of anarchic social orders, and especially so uncompromising advocacy thereof, might cost libertarians valuable partners and allies in the fight for freedom. People might be much more likely to accept libertarian positions if those are not presented as “either-or”-questions, but merely as practical proposals to improve the status-quo.

In short, it is highly unlikely that anarchy a) would lead to superior economic outcomes than present forms of governance in western countries, b) should be considered as a stable equilibrium in human affairs and c) constitutes a clever strategy for libertarians to pursue. Lovers of liberty who focus too much on implementing and/or talking about it, risk crowding out valuable potential partners and alienating themselves further from today’s mainstream by not offering practical solutions to current social problems.

These pieces solely express the opinions of the authors and not necessarily the organization as a whole. European Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, please contact mhemelrijk@old.studentsforliberty.org for more information.