Building Casual Libertarianism

Libertarians have been frustrated for a long time by the inability to overcome a perplexing hurdle. Over the years the liberty movement has grown (especially with young people) and libertarians have played an important role in pushing conservatives and progressives to promote liberty on key issues like criminal justice reform. But, frustratingly, all of our success comes from convincing others of the importance to act. Libertarians haven’t had the popular strength to act independently to make the world a freer place. This is frustrating because you can only do so much with persuasion, mostly effecting change at the margins and where the benefits of liberty are the most obvious.

This problem comes from the nature of the libertarian movement. Polls and research indicate that libertarians are at least on par with progressives and conservatives when it comes to how many people’s beliefs align with the ideology. But many of these people align themselves with the conservative and progressive movements instead of libertarianism. This means that, although they may be prone to support libertarian causes, their support ends up fueling conservative and progressive causes instead.

So libertarians need to figure out (1) why people with libertarian leanings don’t identify with libertarianism, and (2) how to get these people to identify with libertarianism.

There are probably multiple reasons why people don’t identify with libertarianism, starting with people not knowing what libertarianism is. But the big issue that lies at the root of the problem is the comfort people have with an ideology. It can be easy for activists to forget sometimes, but most people aren’t very political. People have beliefs about politics that they hold and share – but the importance they place on politics is much lower than they place on other parts of their lives. This (ironically) hurts libertarianism because libertarians usually aren’t like this. Libertarians have usually done more homework on political things, and are more invested. If somebody identified themselves as a libertarian, you would probably assume that they were more invested in that belief than if they identified themselves as conservative or liberal. This is the result of a rut in which libertarianism is perceived as niche, and as a result only people with that niche identify as libertarian – making the perception accurate and continuing the cycle.

This is where conservatism and progressivism gain the upper-hand in the broader scheme. It is likely for someone to be a casual conservative or a casual progressive, where it isn’t likely for someone to be a casual libertarian. And this is where the respective movements get a lot of their strength. The number of conservatives who have read Burke, Kirk or Buckley is probably less than (even in absolute terms!) than the number of libertarians who have read Mises, Hayek or Rand. But conservatives simply aren’t expected to be so invested, because there is a casual variant of conservatism to identify with.

If libertarians want to start effecting change by themselves, without needing to rely on temporary allies, the persona of libertarianism is going have to become more casual. Something that people can identify with, but not be expected to devote significant portions of their lives to. This may seem like blasphemy to some. But the whole point of libertarianism is that people should spend less time paying attention to politics, and focus on their own lives and communities. We just have to get people to turn their inattentiveness regarding what’s happening in government to a default NO.

As far as changing libertarianism’s persona – I don’t have direct answers. But I can offer warnings. While I think libertarianism should be a more casual movement, there are very serious consequences that can arise from moving recklessly in this direction. We should look at the history of conservatism for insight here.

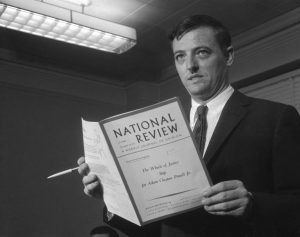

Magazine editor William F. Buckley, Jr., holds a copy of National Review as he makes a statement on the steps of the U.S. Courthouse. (Copyright Bettmann/Corbis /AP Images)

Edmund Burke, Russell Kirk and William F Buckley Jr. are the intellectual founders of the Conservative Movement in the United States. The Conservative Movement followed the path that I think libertarians ought to follow; and conservatism went from being a fringe movement in the 1950s to nominating a major party candidate in 1964 (Barry Goldwater) and electing a President in 1980 (Ronald Reagan). Since the 1980s, Conservatism has almost completely lost its intellectual base. During the 1990s, conservatism saw an even bigger influx when Talk Radio came on the scene. This helped make Newt Gingrich Speaker of the House of Representatives in what was known as the Republican Revolution, by mobilizing millions of people to conservative candidates. This influx seemed great for conservatism at the time, but in retrospect we can see that to achieve this surge, Talk Radio abandoned conservatism’s intellectual base and replaced it with cheap populist rhetoric. This change has manifested itself today in intellectual conservatives losing the Republican Party to pure rhetoric and anti-intellectual-emotionalism. As mentioned before, the conservative intellectual tradition is mostly forgotten to most self-identified conservatives today.

Libertarians should aim to make the intellectual movement matter by expanding the ideas to a more casual audience, but not destroy the message by tailoring the intellectual movement to tailor to cheap rhetoric and emotion. The Conservative movement built itself up from the 50s to the 80s by translating intellectual ideas into consumable media with outlets like the National Review. Libertarians should look to this as a guide, but tread carefully not to repeat Conservatism’s mistake and begin to extrapolate the ideas from the rhetoric.

This piece solely expresses the opinion of the author and not necessarily the organization as a whole. Students For Liberty is committed to facilitating a broad dialogue for liberty, representing a variety of opinions. If you’re a student interested in presenting your perspective on this blog, visit our guest submissions page.