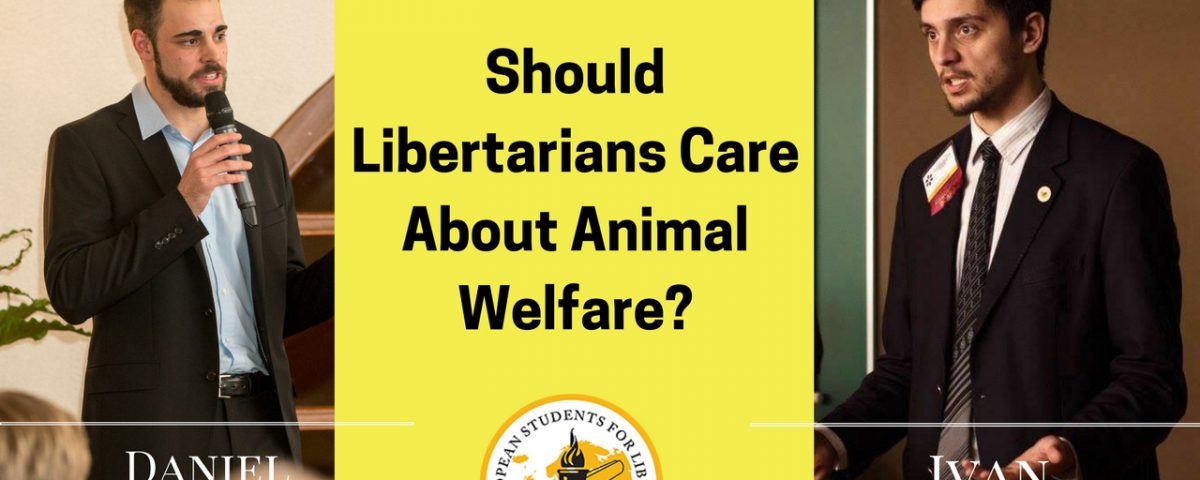

In this Liberty Face Off, Daniel Issing and Ivan Bertović discuss Animal Rights: Should libertarians care about animal welfare?

Classical Liberals are Ignorant About Animal Welfare, and for No Good Reasons

By Daniel Issing

In his Principles of Morals and Legislation, Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, famously argued that his philosophical predecessors had been unduly negligent in their treatment of non-human animals. Decrying them for their insensibility, he writes: “The day may come, when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of skin is no reason…the question [whether something should be a subject of moral philosophy] is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” And while most of his contemporaries regarded these paragraphs as outlandish when they were written, his reasoning has stood the test of time and is still used as a basic reference line in moral philosophy.

It has always struck me as odd that so many libertarians would turn a blind eye on the issue of animal welfare, given that they are usually very interested in philosophy and care a lot about human rights and peaceful interaction. Maybe they are bewildered, understandably, by the campaigns of organizations such as PETA. Maybe they are, like most other people, just too lazy to question something they habitually do and enjoy. Maybe they fear more governmental interference in their lifestyle. Whatever the reason is, it is not enough to restrict animal rights based on their limiting of human action, for the same is true of other horrible actions such as murder and robbery. It is clear that if there is a violation of rights occurring, it must end.

For one thing, it is basically undisputed that inflicting a great deal of pain on animals for modest gains in psychological satisfaction, or even for no reason at all, is morally unacceptable, as even high-profile critics of animal rights such as Tibor Machan admit. Robert Nozick asks why a similar point shouldn’t also hold for the pleasure derived from eating animals: “The gain, then, from the eating of animals is pleasure of the palate, gustatory delights, varied tastes […] The question is: do they, or rather does the marginal addition in them gained by eating animals rather than only non animals, outweigh the moral weight to be given to the animals’ lives and pain?” We already denounce killing animals for a number of reasons and deem unacceptable practices such as the blood hunt or ritual sacrifices. We feel outraged if someone tortures his pet to get sadistic satisfaction. Do we exclude eating animals from the list because it personally affects us?

While unlikely, it is certainly conceivable that human utility derived from eating meat is greater than the costs imposed on animals (It is unlikely because even if you attribute extremely low importance to animals in ethical considerations, the suffering caused by the meat industry, slaughtering between 40 to 60 billion creature worldwide per year, is still astronomically huge.). But arguing along these utilitarian lines is a slippery slope: What if the same were to hold true for cannibalism? Few of us are ready to ultimately sacrifice individuals for the coherency of their utility calculus, and are much more comfortable with a Kantian outlook that views human beings never just as a means, but always as ends in themselves. Which directly leads to the question of where to draw the line.

The point is this: Even if you were to conclude that all things considered, we really shouldn’t care what consequences our behaviour has on animals, you would still have to argue why only they should be excluded from such considerations. What criteria will you use? “They’re not humans/part of the human species so they don’t have the same rights.” That’s not even an argument, it’s just arbitrarily putting a label on something to reassert what you believe. “They do not have ability to reason.” Neither does a human baby. “They won’t become a reasoning entity later in life.” The same holds true for a severely mentally challenged person or a severely senile old person. “It’s a convention that has stood the test of time.” This could have also been said to justify the institution of slavery two centuries ago. Whatever rule you pick, it’s not hard to come up with human counter-examples that carry monstrous implications. The takeaway is that if you want to be serious about political or moral philosophy, you can’t simply evade these questions.

What about health issues? I concede that it would be unreasonable to ask someone to change his diet if likely consequences include a shorter lifespan and a significantly increased risk of falling ill with a dangerous disease. But this clearly isn’t the case here. At best, the research is inconclusive, while there is growing evidence that especially vegetarianism is healthier than a meat-based diet. Except in very rare cases, citing health effects to justify meat consumption is hardly more than a self-serving excuse.

I’ve met people who agree with most of what I wrote here and yet dismiss it because they consider it a relatively irrelevant matter. I’m not necessarily disputing that there are more urgent things out there. But in contrast to these loftier goals, you can personally make a traceable difference when it comes to animal rights. For example, it is estimated that the average American meat-eater consumes the equivalent of roughly 2,100 chicken, 70 turkeys, 30 pigs, 10 steers and 1,700 fish – just picture the number of lives that could have been spared by your own decision. It’s about time to rethink the prevailing attitude.

Daniel Issing is a Charter Team Associate with Students For Liberty.

To Meat or Not to Meat – It’s a Personal Question

By Ivan Bertović

The quality of an argument can best be measured by taking that argument to its most extreme conclusion, and seeing if that is something we find reasonable. Most of the arguments we hold dear are valid even in the most extreme cases, such as free speech, but those that cannot hold up to this scrutiny must be committed to the flames, to borrow from Hume. If premises are corrupt, our conclusions will most likely also be.

That is why there’s absurdity that can’t be justified in the argumentation of application of libertarian principles, as a general rule for all liberty lovers to abide by, to any life form other than humans (at least for now).

The most common arguments why animal welfare needs to be reaffirmed and more actively implemented into any idea are:

- Animals are living beings too

- Animals feel pain

- Animal-based products are not necessary

There is no doubt animals are living creatures, as they share all relevant characteristics. Yet equating an animal life with the one of the human has implications that one would find absurd regardless of their moral framework. If animal life is a life worth protecting because it inherently has the same or similar value to the human’s, then what is the essence of that value? How do we differentiate what constitutes a “worthy” life. Is it reserved purely for mammals, do we include lizards as well, do we fall all the way to single-cell organisms because in the essence they are also alive. Plants are also considered “alive.” One would not last long in the world respecting every life the same way we respect human. Our every breath would be considered a genocide. Such implications would also reflect on our perception of other, more sentient, life. Do we, in that case, value the life of a hardened criminal with the one of an innocent child? They are equal before the law, but are they equal after the law passes judgement? It’s absurd, I know. That’s how we test it.

The argument from pain is, in my view, equally unstable in the face of the challenge. If the pain is the benchmark, one can easily think of ways this could be used to take life even if it is valued in Western value system. Even plants react to the destruction of their tissue, which we perceive as pain. They hear caterpillars nibble on them and activate their defences, where we would fight back. They release scents into the air when attacked to attract bugs that will defend them, where we would scream for help. They share information on incoming attackers, where we would warn of incoming enemies. They present a form of conscientiousness that would make them included within the lives worth defending.

And finally, the fact that we can live without meat. I am no expert on nutrition, I have no clue about agriculture and farming, or of any data on the sustainability of the all vegan diet implemented through economy of scale. But I do know a bit about supply and demand. Our “needs” come from our “wants.” If you want to live, you need to eat. Some argue that a human can survive off of plants alone in a sustainable economics model. But the fact of the matter is, there are consumer goods that are derived only from animals, and in order to substitute them, one needs to produce these substitutes which in turn have higher price since the more effective and efficient producer already existed. The animal itself. Thereby we actively transfer the cost of surviving from animals onto humans, and preferentiate animal life over the human life. Yet even then one might argue that not every animal’s welfare is being observed. For us to have massive fields, birds lose their habitat, and mice are being run over. Bugs and other pest are murdered by the thousands in an attempt to preserve our food supplies. I wouldn’t dare to presume that animals understand the NAP* and that by violating it, i.e. entering our fields, “had it coming,” in the same way that I wouldn’t expect it from a child. I also wouldn’t drive over a would-be thief in the field with my farming machinery, but that’s beside my point.

The reason why we apply the NAP and other libertarian principles onto some who lack conscientiousness is either because we expect them to develop it in certain point in time, like children, or because we respect their personhood, as would be the case with a coma patient for example. All of the previously stated arguments are not to say that animal welfare is irrelevant. It is among some of our “wants.” I myself have a dog, and I love her dearly. The tail-wagging and excited jumping to greet me whenever I come home from work brings joy to my life for which I’m immensely grateful to her. I would not let anyone or anything to harm her. I want to see less animals suffering on crowded farms where they are skinned, boiled, and cut open alive, where they are terrified and crammed into tiny spaces in conditions that seem inhumane even if plants were in their places. And I adjust my consumer preferences according to that. But libertarianism is here to empower people. To give way for their “wants.” Libertarian might want a car, yet none would argue that owning a car is essential to libertarianism. I do not dismiss animal welfare, but it should not be conflated with libertarianism. Let’s call a spade a spade. Let thousand ideas bloom! And who knows, perhaps the idea of animal welfare is the “superior” one. But not to the idea of Liberty.

Ivan Bertović is a former European Students For Liberty Executive Board member.